April 1961: President Kennedy sits with the brightest minds in American foreign policy: Dean Rusk, Robert McNamara, McGeorge Bundy. These were smart, accomplished people who got to where they were not because they were accustomed to being wrong but usually because they were really good at being right.

The plan was simple: land 1,400 Cuban exiles at the Bay of Pigs, spark a revolution, topple Castro. Everything made sense.

And if you were sitting in that room, you would be surrounded by people all nodding along to one of the worst military plans in American history.

Enter the Skeptic

Except one. Senator J. William Fulbright had made it a habit of asking questions, challenging assumptions, and raising long lists of potential problems. He even wrote Kennedy a letter explaining why the whole thing seemed like a terrible idea.

That prompted Kennedy to invite him to voice his concerns directly to the group.

And that's when things got interesting. Because the more Fulbright objected, the more confident everyone else became. In fact, it was as if his very presence allowed everyone else to feel they'd heard the counterarguments and could move forward undeterred with clear consciences.

Fulbright had become what social scientists call the "designated skeptic"—the person who carries all the group's doubts so everyone else can stop worrying.

Three days later, the invasion collapsed completely.

Days later, Kennedy famously asked, "How could we have been so stupid?"

The Daily Reality

This exact same dynamic plays out in college and university leadership meetings every single day. Higher education is, after all, fueled by consensus-driven decision-making. Committees for everything. Cultures that prize getting everyone on board. A constant appeal to mission—"this aligns with our mission so how could you disagree"—even when nobody's quite sure what that mission actually means.

Everyone seems to think they're all on the same page.

So here's what happens when you're the person who dares to speak up in that type of setting: You become the one finding problems that people feel they've already solved in their heads. You become the one pushing back against what everyone already believes to be the agreed-upon way forward. You're asking questions in a way that might even be seen as challenging authority, even if you're convinced those people in authority haven't really thought the decision through.

If that's you, here's what you need to know.

You're Inside a Collective Illusion

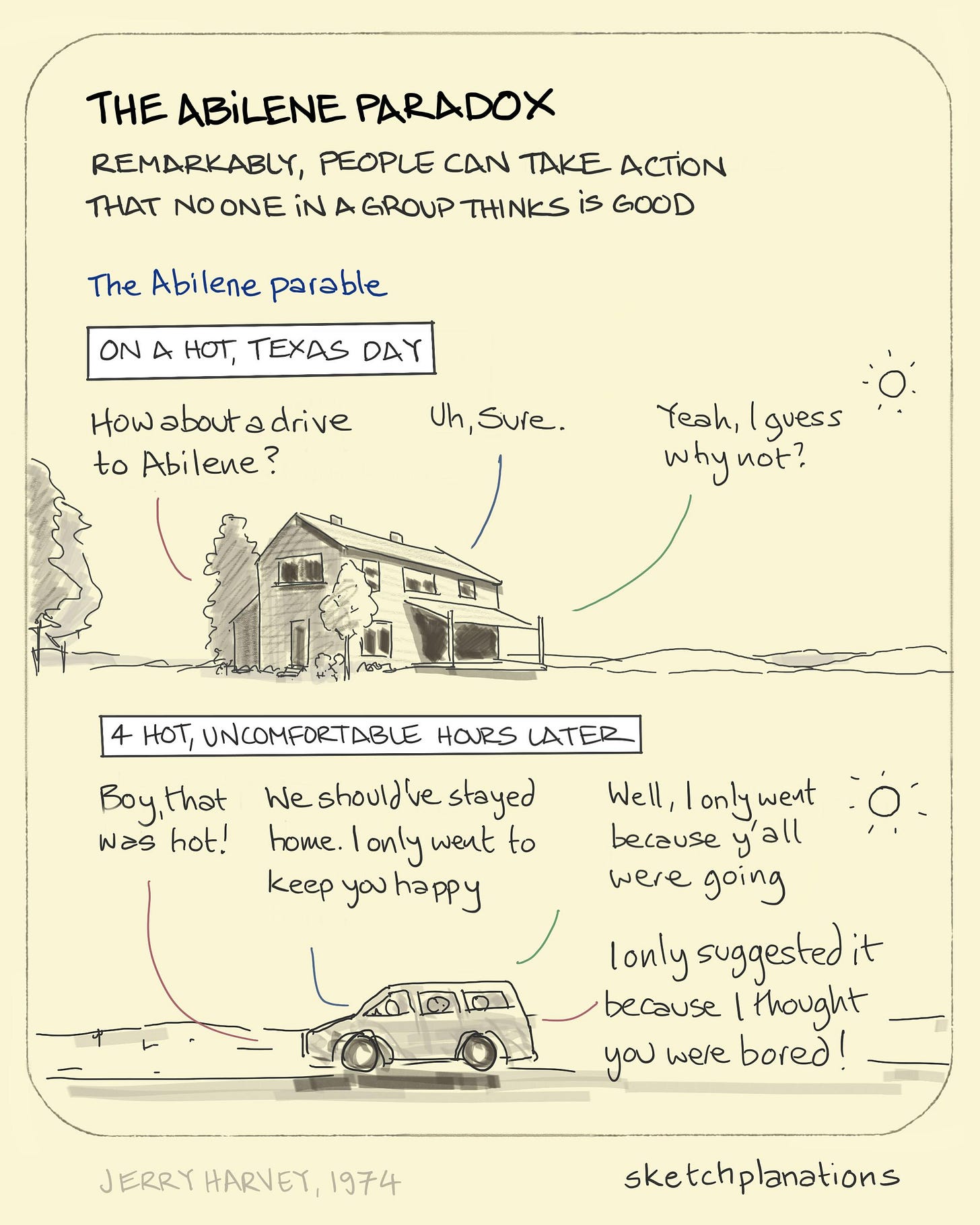

Back in the 1970s, a management professor named Jerry Harvey told a story that became famous in business circles. He called it the Abilene Paradox.

Harvey's family was sitting on a porch in Texas on a hot summer day when someone suggested they drive to Abilene for dinner. It was 100 degrees. The car had no air conditioning and Abilene was 50 miles away.

Nobody actually wanted to go, but each person assumed the others did, so they all agreed.

So they drove to Abilene, had a terrible meal, and drove back home even more miserable than before. And only then did they discover that not one person had wanted to make the trip. Not in the hot sun before leaving, not in the hot cramped car, and not even at the restaurant. They'd all just gone along with something nobody wanted because everyone thought everyone else wanted it.

Harvey used this story to explain why organizations make bad decisions. I've referenced it hundreds of times.

But I've often wondered what exactly was going on in the minds of the people on that trip to Abilene?

I recently picked up Todd Rose's book Collective Illusions, and it completely changed how I think about this paradox. What Rose discussed decades later would delve into the psychology behind it, not just what happens in groups, but also what's going on inside each person's mind.

You know those uncomfortable moments in meetings? Rose discovered that we're actually wired to care more about what we think other people think than about what we think ourselves. It's not just about going along with the group. It's about misreading the group entirely.

Here's How Collective Illusions Work

You're sitting in that meeting about the new strategic initiative. It sounds half-baked to you, maybe even wrong, but everyone else seems enthusiastic. So you stay quiet. Meanwhile, the person next to you is thinking the exact same thing, but they're staying quiet too because they think you're enthusiastic. Same with the person across the table. And the one by the window.

You’re halfway to Abilene.

Everyone thinks they're the only skeptic. Nobody speaks up. The group makes a decision that maybe nobody actually wanted.

Rose explains it this way: "We've all had those moments where we think we're the only one in the room that holds a view. Rather than speak up, we say nothing, and we're not alone."

Sound familiar?

What to Do: Break the Silence

The solution isn't to become a better designated skeptic. It's to realize that your silence might be part of the problem.

Rose's research shows that when you speak up authentically, not as the person who "always finds problems" but as someone sharing genuine concerns, you often discover you're not alone. Your voice gives others permission to share what they're really thinking.

The goal isn't to be the contrarian. It's to break the illusion that everyone else has already made up their minds.

Sometimes the emperor really isn't wearing any clothes. And sometimes you're not the only one who noticed.

Try This Next Time

If you're tired of watching your institution make decisions that feel like endless trips to Abilene, here's what you can do:

Ask a simple question. Next time you're in a meeting where everyone seems to agree but something feels off, try this: "Before we move forward, let me ask: does anyone have any concerns about this?" Then wait. Really wait. Count to ten in your head. Make it awkward. Chances are, you'll be amazed how often someone finally speaks up.

Share your own uncertainty first. Inevitably, the conversation will turn back to you. When it does, instead of presenting your concerns as facts ("This won't work because..."), try sharing them as questions ("I'm wondering if we've thought about..."). When you model uncertainty, others feel safe to admit they're not sure either.

Follow up privately. After the meeting, grab coffee with someone who seemed quiet. Ask what they really thought. You might discover they had the same concerns you did. Next time, you can speak up together.

The point isn't to torpedo every decision. It's to make sure the decisions you make are actually the ones people want to make, not just the ones people think everyone else wants to make.

Because there's a difference. And that difference matters.